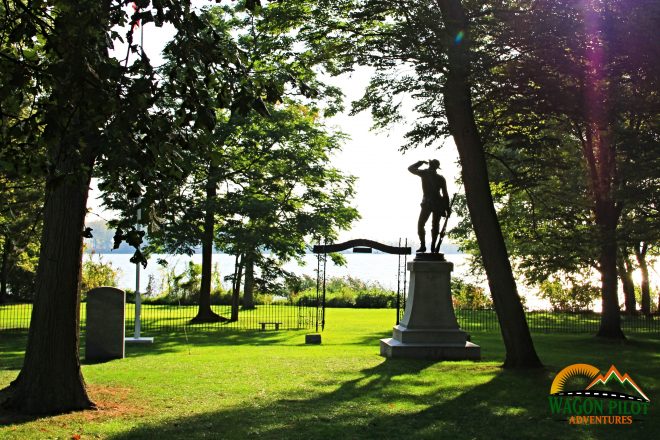

A Confederate soldier stands guard on the shore of a tiny island in Lake Erie. Unlike the massive column immortalizing Commodore Perry’s victory over the British in these waters, this is but a simple soldier keeping watch over his brothers who never made it home after the Civil War. Following his gaze, there’s a bit of irony as he looks out towards the Cedar Point amusement park. Thrill seekers there likely never knowing a prison camp sat right across the water on Johnson’s island. The cemetery here is little known outside of the community, yet is an important and rare reminder in the Midwest of the war that nearly shattered the country.

Johnson’s Island Prisoner of War Camp

Half of Johnson’s Island, named for the then current owner, was leased by the US Government in 1861 for use as a prisoner of war camp for Confederate officers. By April, 1862 a roughly sixteen acre compound, surrounded by a stockade of wood poles, was in place. Two-story barracks were built within the camp as prisoner housing, with additional buildings outside for Union troops, storage, and camp operations.

The 128th Ohio Volunteer Infantry guarded the camp, which was designed to hold up to 1,000 prisoners. By 1863, the system of prisoner exchanges between the two sides had broken down and more inmates needed to be held in camps. Johnson’s Island, as well as Camp Chase in Columbus, saw their numbers swell. Prisoner population peaked at around 3,200 in the camp during the next two years and came to include regular soldiers and other dissidents in addition to the officers.

Escape Attempt from Johnson’s Island

Johnson’s Island may have been far away from the war front, but that didn’t mean there was not any risk from the enemy. In the Fall of 1864, a group of twenty Confederates seized a Canadian steamer ship. The plan was to coordinate with a spy to capture the USS Michigan, which was guarding the camp, and use her to free the prisoners. However, the spy was discovered and arrested and the plan abandoned. Throughout the rest of the war, there were a few escape attempts, though none successful.

The Post-War Years

The Civil War ended in April of 1865 and the prisoner population dispersed over the next several months. By November, the Government had left the island. All told, between ten and fifteen thousand prisoners had come through the camp. Surprisingly, less than three hundred had died on the island; which is far less than in other prisoner of war camps.

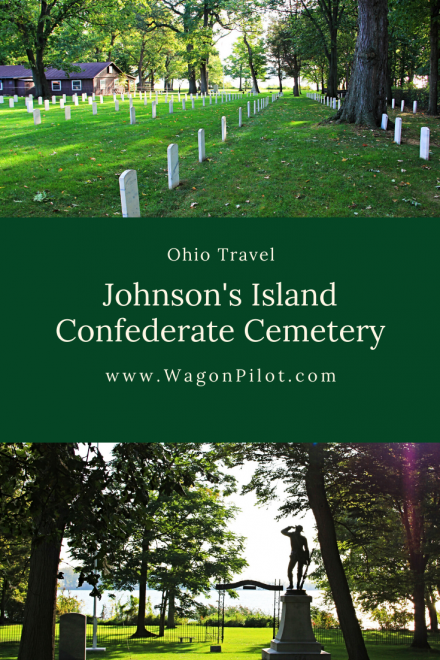

In 1890, citizens from Georgia raised money to replace the wooden grave markers with Georgia marble headstones. There are 206 headstones, though there may be upwards of 240 burials. The cemetery also received a wrought iron fence and archway. In In 1904, the Daughters of the Confederacy purchased the cemetery land and donated it to the Federal Government in 1931. The large bronze soldier statue was erected in 1910. The cemetery is now a National Historic Landmark.

The Confederate cemetery is all that remains of the Johnson’s Island prisoner of war camp today. The one acre of land is managed by the non-profit Johnson’s Island Preservation Society. A museum collection, containing artifacts, letters, etc., is located in the Ohio Veterans Home in downtown Sandusky, Ohio.

Visiting the Johnson’s Island Confederate Cemetery

The Johnson’s Island Confederate cemetery is tucked away between wooded residential lots. The trick is finding your way to the island, since the little side road to the causeway does not have signs. Visitors will also need to have two dollars in cash on hand to operated the causeway’s automated toll gate. Once on the island, just head straight a quarter mile or so and the cemetery will be on your left.

There are a few parking spots next to the cemetery fence along with informative signs detailing the history of the prison camp. There are no facilities available at this location, though the Marblehead Lighthouse park just up the coast is open to the public.

The cemetery itself is in a very peaceful location. Though residential, the area is very peaceful with plenty of old trees. The lot is more long than wide, with the graves near the road. Following towards the lake, the bronze soldier statue stands looking off into the distance. There are a few other small markers in the grassy area next to the lake shore. Standing there, surrounded by homes and an amusement park in the distance, it is difficult to imagine life on the island during the War.

For more information on the location and visitor access, visit the Johnson’s Island Preservation Society website.